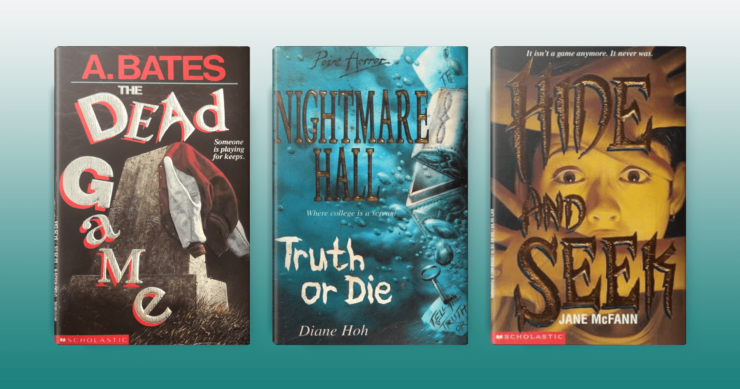

There’s so much subterfuge and deception in ‘90s teen horror, from outright lies and misplaced suspicion to hidden or mistaken identities. People’s motivations are rarely straightforward, your best friend could be the one who’s trying to kill you, and there’s a good chance that pretty much everyone is lying about something, whether it’s where they were last Friday night, who they’ve been making out with behind someone else’s back, or whether they’re secretly terrorizing their classmates under cover of darkness. People are playing a lot of games, but the parameters are often fuzzy and the rules unarticulated. So it should be a refreshing change of pace when the games are out in the open, a fun diversion from all of the murder and mayhem, right? Not exactly. In A. Bates’ The Dead Game (1992), Diane Hoh’s Truth or Die (1994), and Jane McFann’s Hide and Seek (1995), the stakes of these games are high: you lose, you die.

In The Dead Game and Truth or Die (#15 in Hoh’s Nightmare Hall series), the games start out innocently enough, as a bit of friendly fun and a way to pull some pranks on people who arguably really do have it coming. In The Dead Game, Linnie, Ming, and Jackson pick out a handful of their classmates to “kill” by publicly humiliating them: there are two twins, Adler and Austin, who transferred to their school senior year because the AP credits they’re transferring in will allow them to grab the valedictorian and salutatorian spots, knocking Ming out of the top spot and bumping her down to number three. Ladies’ man John uses sleazy lines on all the girls in school, gets them to go out with him, then dumps them and spreads rumors about them, ruining their reputations. Brenda is a quintessential mean girl, going out of her way to tear her peers down and make them feel bad about themselves. As Linnie, Ming, and Jackson figure, if someone were to give their classmates a taste of their own medicine that’s really not so bad, is it?

It’s all fun and games to start, but when one of their targets, Rafe, gets food spilled all over him in the cafeteria and takes a bad fall, he doesn’t get back up. The ambulance comes, Rafe is hurt but not killed, and the three friends basically shrug it off as a fluke and keep playing. Jackson strikes gold when he sees Brenda steal a bracelet from the mall, but when he spills this secret in the cafeteria, she flees in horror, falls down the steps outside of the school, and dies. Horrified by this tragic turn of events, the trio stop playing—but the hits keep coming, and their new challenge is to figure out who has decided to keep playing the game, with or without them.

Buy the Book

Spring’s Arcana

Hoh’s Truth or Die starts just as innocently (at least as far as Salem University freshman Parrie Moore can tell). Parrie meets a group of other freshman girls—Carol, Jean, Mallory, Lil, and Grace—who are bored at a start-of-term tea party. To liven things up a bit, they start an old-school game of truth or dare, with the inaugural dare to switch the sugar on the tea table with salt. Hilarity ensues (obviously) and Parrie feels pretty great about having met some people and made some friends. Right up until one of the girls, Carol, proposes that they each write their deepest, darkest secret on a piece of paper, put those secrets in a lock box, and then basically use those secrets as blackmail fodder to fuel an increasingly high-stakes game. These girls must have some pretty horrifying skeletons in their closets, because they’re willing to do all kinds of ridiculous dares. Grace is dared to go to one of their professor’s houses and let the air out of his car’s tires–but while she’s hiding in the garage, someone starts the car and locks her in, leaving her to asphyxiate. Parrie is dared to sneak into and spend the night alone in Nightmare Hall, and when Jean comes in and tries to scare Parrie, someone else follows Jean in and hits her on the head, giving Jean a concussion and landing her in the infirmary. But the girls still keep playing. While stubbornness and a fierce competitive streak are part of the reason they persist, Parrie also explicitly notes that a big part of it is peer pressure: she has friends, she wants to fit in, and to do so she’ll keep playing the game, long after she wants to stop.

In both The Dead Game and Truth or Die, things aren’t exactly what they seem and the other players can’t be trusted. In The Dead Game, Linnie, Ming, and Jackson decide that someone must have been eavesdropping on them when they planned the game and that the mystery person just kept running with it after they had decided to stop. They put their heads together to figure out who it could have been and decide that the only reasonable course of action is to go to the police and tell them everything they know. Linnie is worried that this mystery person may have listened in on their plan to go to the police as well and be lying in wait for them, so she goes to their rendezvous point early to make sure the coast is clear … and to lie in wait, because she’s the one who has been doing all of the terrible things. Linnie attacks both Jackson and Ming, taking them by surprise and ready to kill them, though Jackson and Ming end up saving one another. When the truth comes out, they learn that Linnie likely pushed Brenda down those stairs (Brenda could technically have fallen down the stairs—Linnie’s not telling, one way or the other) and Linnie was ready to kill them both because… well, there’s not really a great reason, actually. Linnie has a complicated relationship with her older sister, who has always done bad things and blamed them on Linnie, but those bad things have been stuff like breaking a vase or stealing money from their mom’s purse, not murder. She wants to “matter” (152) and she wants to be famous–but not famous for murdering people, because she wants to stay free to keep on murdering to bring the people she sees as cheaters and fakes to some sort of vigilante-style justice. Linnie is arrested, and when her parents reach out to Jackson to tell him that Linnie’s really not a bad person, just misunderstood, Jackson and Ming seem to agree, with Jackson remarking that “I’m not angry, I’m just sad” (165) and Ming coming to the conclusion that “She wasn’t evil. She was just Linnie” (165). And that, presumably, is that. There’s no sense of what happens next, whether Linnie will get the help she needs or be brought to justice herself, and Jackson and Ming move on to their next game, of figuring out how a brain and a jock can make love work in this crazy world.

In Truth or Die, Parrie has a similar realization that there’s more going on than meets the eye and discovers that she’s really just a pawn in a much larger game. In the climax of the book—somewhere around the third repetition of the truth or dare game, because some of the girls really just won’t let it go—she finds out that the other girls all know one another and have a dark secret from their shared past. The other five all went to summer camp together as adolescents, and while they were a close-knit group for the most part, Mallory was the odd girl out, excluded from the orbit of her more popular peers. And while this would perhaps suggest that Mallory’s out for revenge and to make them pay for this long-ago slight, the opposite is actually true, with Mallory appearing as both victim and (quasi)villain, both in their childhood experience and in this new game of truth or dare. While Mallory was an outcast at camp, she wasn’t the only one, and another girl named Jennifer was endlessly trying to break into the ranks of the cool girls’ group. They teased Jennifer about an initiation ritual, putting her off and never really intending to follow through, but when Mallory overheard them joking about daring Jennifer to jump from the lake’s high dive at midnight, she told Jennifer, goading her into this dangerous and foolhardy plan, which leads to Jennifer’s death. The girls blame Mallory, and while Mallory holds them all responsible, when she tells her side of the story she points the finger at Jillian (who in college calls herself Lil), because Jillian is the one she hates the most. They all carry this trauma as they grow up, though it is the worst for Jillian/Lil, who tells Mallory that “You were responsible. But I am the one who paid. People looked at me. People pointed and whispered. It was a scandal. My parents had to move to another town. I grew up being treated like a criminal for a crime I didn’t commit” (149, emphasis original).

This shared history leaves each of the girls committed to the idea of ferreting out the truth, which is the common goal of their increasingly dangerous game of truth or dare, though their versions and perceptions of the truth are quite different: Mallory wants Jillian/Lil and the others to acknowledge how unkind they were to her at camp and share the responsibility of Jennifer’s death, while the other girls want Mallory to face up to what she did and to the deadly consequences of her actions. Parrie is just caught in the middle, stopping to chat with the wrong group of girls at that awful tea party, a chance encounter that results in her being drawn into their manipulative game and nearly dying when Mallory tries to push her off a cliff during the girls’ final confrontation. After this whole disaster, the girls decide they want to be friends with Parrie for real, rather than just as a pawn in their game or protective coloration, and to her credit—and character development—Parrie turns them down. When Grace comes to plead her case, Parrie tells her “I don’t know if I want to be part of your crowd. Or of any group of people, for a long, long time. Maybe even never” (161), silently congratulating herself after Grace has left with the realization that “Once upon a time … I wouldn’t have been able to say that. Once upon a time, I would have agreed to anything to keep a friend. Any friend. But not anymore” (162). It takes almost being killed to break Parrie out of her people-pleasing habits, but she gets there in the end. And she did meet a cute boy along the way, which is presented as an at least okay consolation prize when it turns out that all her new girlfriends see her as collateral damage in their terrifying game.

McFann’s Hide and Seek is in a league of its own and is legitimately horrifying on multiple levels. Unlike the protagonists in The Dead Game and Truth or Die, Hide and Seek’s Lissa has no interest at all in playing any of these games and when she’s hiding, it’s because she is literally trying to survive. Almost the entire book is presented through a series of flashbacks as Lissa cowers in her hiding spot, listening for the footsteps of the person trying to kill her, and anticipating her death at any moment, resigned to its inevitability. And unfortunately, Lissa has a wealth of lived experience that have led her to the fatalistic conclusion that her impending death is unavoidable and that no one is coming to save her.

Lissa grew up isolated in a house with her passive mother and her temperamental, violent father. Lissa’s father is an artist and she and her mother live their lives tip-toeing around him, unsure of what may cause his next outburst; he is emotionally and psychologically abusive in his relationship with Lissa and she lives in a constant state of terror. She is expected to be quiet and unobtrusive at all times, with her presence and needs never infringing upon her father’s view of a perfectly-ordered world designed to meet his every whim. When Lissa’s mother points out to him how beautiful Lissa’s hair looks as she braids it, he cuts off one of Lissa’s braids and from that point forward, her hair is kept dramatically short. He is cruel in his assessment of her artistic skill, looking at one of her drawings and telling her that she’s terrible and will never be any good. When she comes home with straight As on her report card, hoping to prove her worth and earn his love, he dismisses her achievement, saying “What can be hard about sixth grade? Anybody can do well down at that level” (64). As Lissa grows up, her father’s abuse escalates: he pushes her down the stairs and breaks her leg, he attacks her pet bird (named Bird), and he attempts to strangle her. His cruelty toward Lissa is thrown into stark relief when Lissa has the opportunity to see him speaking with other people outside of their family at a gallery opening, in an interview with a local reporter, and when a classmate’s mother drags the girl by the house unannounced, demanding an artistic analysis of her daughter’s work (which he effusively praises, offering heaps of encouragement, though the girl’s work is amateurish and awful).

While Lissa’s mother has made justifications for his behavior in the past—even instructing Lissa to say she tripped on the stairs and putting her sweater on Lissa to cover the bruises on his arms from where her father grabbed her when they go to the emergency room to get her broken leg set—the attempted murder when he strangles Lissa finally spurs her mother to action, and she takes Lissa and Bird on the run. But even this isn’t the new start that Lissa hopes it will be, as she soon discovers that when she goes to school, her mother drives the four hours back to their house to be with her father, returning by day’s end to care for her traumatized child. Lissa understandably struggles with the fact that even when her life is in danger, her mother won’t choose Lissa over her father, but she doesn’t become hysterical or even angry, accepting her mother’s commitment to her father with a kind of detached and defeated resignation, only asking that her mother promise not to let her father know where Lissa is. And while Lissa’s mother seems to keep this promise—it’s the transcript sent from her former high school to her new one that provides the breadcrumbs he follows—he finds her, luring her into the woods with Bird and then essentially stalking her through the wilderness, a pursuit she is only able to escape by burrowing into the hollow provided some roots at the base of a tree trunk, covering herself with dead leaves, and waiting for him to find and kill her.

As she cowers in fear, she thinks back through her life, trying to figure out what brought her here and (heartbreakingly) what she believes she did to cause or deserve it. While Lissa is ingenious in keeping herself hidden, these thoughts paralyze her and it’s just a matter of time before her father will find her—until Josh, a nice, persistent guy from school who is worried about Lissa (and also loves birds) comes looking for her. Josh spots the trouble, mimics Bird’s call to her father off her trail and deeper into the woods, and rescues Lissa. Lissa’s really good at keeping secrets and Josh has no idea what’s going on, but when he sees her in trouble, he does what he needs to help her without a second thought, one of the few and far between authentically good guys of the teen horror tradition.

While many of the books in the ‘90s teen horror tradition don’t dig too deeply into the why behind the violence, McFann does explore and outline the reasons for Lissa’s father’s violence, mainly in his own traumatic childhood (when he expressed an interest in and affinity for art, his father called him gay) and post-traumatic stress disorder from serving in Vietnam. While this background is important and gives Lissa—and the reader—an understanding of her father that they didn’t have before and he begins getting psychiatric treatment in the novel’s final pages, the only options presented for Lissa are either to have an estranged relationship with her father (and by extension, her mother as well) in order to ensure her own safety, or to recommit to that parental relationship with this new knowledge about and understanding of her father, which requires accepting the fact that he will likely hurt or try to kill her again. (McFann’s presentation of PTSD is flawed and problematic in some respects, but it provides a snapshot of the understanding of this disorder in the 1990s, as well as the stigma and silence that often surrounded mental health struggles).

If we are optimistic readers, we can maybe read McFann’s reflection that “He would have to put this behind him now, just as Lissa had to put her past behind her” (199) as an acknowledgement of the complex nature of intergenerational trauma. However, given the events that have come before and the perfunctory way in which Lissa’s father’s PTSD is presented, it comes across feeling more like the message is that Lissa will have to—and potentially should—share the responsibility for her father’s actions and that moving forward, she needs to shoulder the burden of rebuilding (or building) that relationship and forgiving her father. To her credit, Lissa declines this expectation, at least in the short term. Despite her best attempts at remaining isolated in her new life, when Josh’s grandmother offers to take her in as a sort of foster granddaughter, Lissa gratefully accepts. Lissa isn’t willing to pretend none of it ever happened, she maintains a firm distance from her parents with the expectation that her father will do the psychiatric work he needs to do, and in the meantime, “Lissa and Gran baked bread and raked leaves and sometimes, late at night, talked about the really hard stuff. Tiny bit by tiny bit, Lissa felt some of the fear and anger and sorrow leave until she could once again laugh at Bird and talk about her father without crying” (200). Gran provides Lissa with a safe space in which to heal and Josh treats her with kindness, patience, and respect, and in the book’s final pages, the future of Lissa’s relationship with her parents is still uncertain, but Lissa is asserting her boundaries, clearly communicating what she needs, and healing with the help of a supportive chosen family.

Games are central to The Dead Game, Truth or Die, and Hide and Seek, though the stakes are much higher in some of these cases than in others. In all three books, there is a fundamental deception at the heart of the game, with at least one of the players hiding who they really are: Linnie hurts and kills while playing the part of a faithful friend, the girls of Truth of Die conceal their identities from both Parrie and Mallory as they seek their version of justice, Lissa’s father conceals and represses the traumas of his past, and Lissa often has to pretend to be someone she’s not when she’s in public in order to keep herself safe and hide the horrors she faces at home. In these games, the rules aren’t always clear and sometimes the people involved don’t even know they’re playing, though that lack of awareness offers no protection, and even when the rules are a known quantity, they can change suddenly and without warning. While it might be better—and more survivable—to simply not play, for some of these characters, that’s not an option they have. Once the game is afoot, it’s impossible to walk away, and they’re in it until the bitter end: win, lose, or die.